Persistence pays off for kelp farming pioneer

Marine scientist Jo Lane has endured bushfires and the challenges of an emerging industry to successfully breed seaweed for commercial-scale farming.

Jo Lane's mission is to produce food and health products from native Australian kelp, with bonus environmental benefits.

In doing so, she is taking her business, Sea Health Products, and Australia as a whole, into uncharted waters, pioneering commercial kelp farming.

In 2021, Jo won the tender for two new NSW Government marine leases, which could soon be home to Australia’s first commercial kelp farms. But her journey into seaweed aquaculture has evolved over the past seven years, after buying the long-standing Sea Health Products business in southern NSW in 2015.

Sea Health Products relies on harvesting beach-cast golden kelp (Ecklonia radiata) to produce a range of food and health products. After her first year, Jo realised that if she wanted to grow the business she would need to grow the kelp, too. It was the only way to gain greater control over the production of her key ingredient.

But while kelp farming was well established internationally, it was virtually unknown in Australia. And there was no information specific to golden kelp, a brown seaweed native to Australia and New Zealand.

For the past five years, Jo has pursued the necessary scientific and technical information to breed and farm golden kelp. She has’s also developed her business skills through a range of entrepreneurial support programs and successfully applied for several national and international grants.

Her new skills and the grant funding will be critical to scaling up the business – producing kelp seedlings, completing planning approvals and getting farm infrastructure in the water.

“To farm kelp, you need kelp babies, and you need somewhere to grow them. We’re making progress on both of these.

We’ve had success with the breeding, which has taken five years, and now we’ve also had some success with the beginning stage of the leases. It's all coming together.”

Jo Lane with golden kelp collected on the beach. Photo: Honey Atkinson.

Jo Lane with golden kelp collected on the beach. Photo: Honey Atkinson.

Golden Kelp powder is produced from sea kelp hand-harvested from waters off the south coast of NSW and ground down to a fine powder. Photo: Sea Health Products.

Golden Kelp powder is produced from sea kelp hand-harvested from waters off the south coast of NSW and ground down to a fine powder. Photo: Sea Health Products.

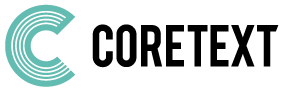

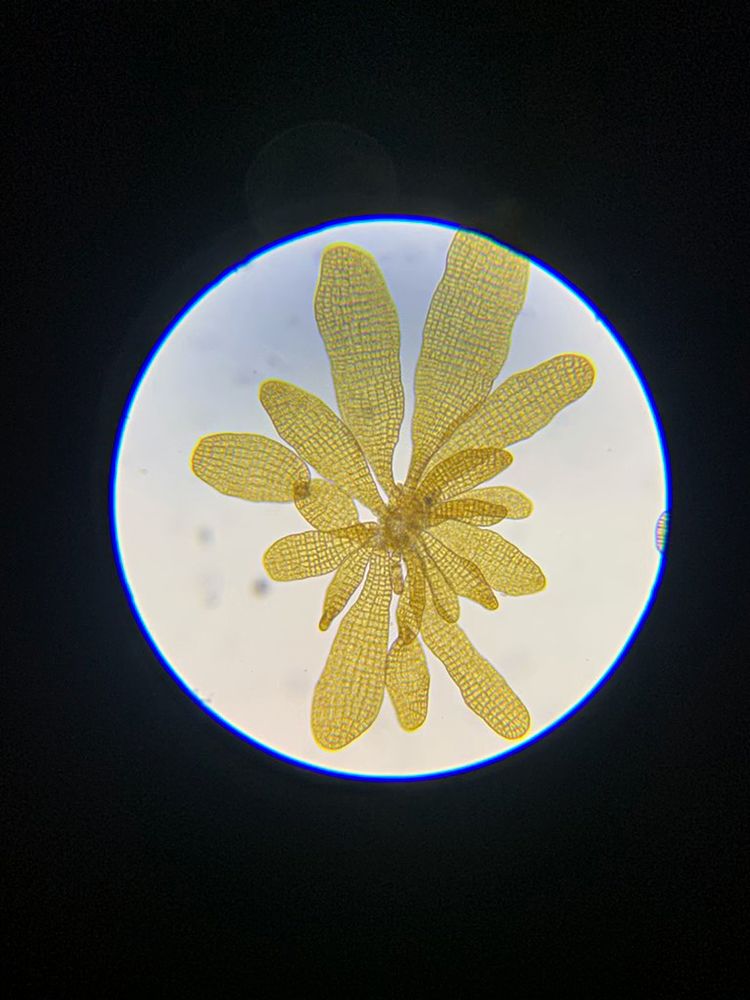

Baby golden kelp. Photo: Sea Health Products

Baby golden kelp. Photo: Sea Health Products

A bigger seaweed vision

When Jo bought Sea Health Products from its original owner, it was something of a lifestyle choice. It was a boutique business in an idyllic part of regional Australia, which drew on her knowledge and love of the marine environment and her desire to promote the benefits of seaweed for good health. Golden kelp is packed with more than 60 essential vitamins, minerals and trace elements, particularly iodine and calcium.

These same factors are driving her efforts to establish kelp farming and to contribute more broadly to the emerging seaweed sector in Australia.

Internationally, the ocean farming of seaweed is a major industry. Seaweeds and related extracts were valued at $US2.65 billion in 2019 and growing. But it is early days in Australia. Only a handful of farms have been established over the past three years, none of them farming kelp. Research into seaweed species for farming and appropriate farming techniques are still in their infancy.

With little information about kelp farming available locally, Jo headed overseas in 2019 on a three-month Churchill Fellowship study tour. She visited Korea, Ireland, Scotland, Norway, Faroe Islands, the US and Canada. Seaweed farming is dominated by Asian nations, which produce 97% of global supply. Jo found small industries also gaining momentum in Europe, the UK and the US.

She returned confident that farming golden kelp was doable in Australia and she had a clearer vision for her business. After returning, she took part in the Bega Valley Innovation Hub 12-week business accelerator program funded through AusIndustry’s Entrepreneurs’ Programme. Her focus was on the idea of introducing kelp farming to NSW, and her business pitch in the final week won both the Judges’ Choice and the People’s Choice awards.

But just a month later she and her family found themselves in the midst of the Black Summer bushfires. Their home and business in Tilba Tilba on the NSW coast escaped the fires, although they evacuated four times during January. They also lost their harvest that summer, along with the propagation research they had underway.

In the aftermath of the fires, Jo also received assistance from the Entrepreneurs’ Programme Strengthening Business initiative, which was run through the Bega Valley Innovation Hub and its networks. The Strengthening Business initiative had been developed specifically to help bushfire-affected businesses to recover and improve their resilience to future challenges. “We had access to a mentor for 12 months and that was very valuable."

“Basically, I’m a scientist, a conservationist. The business side of things doesn’t come naturally to me, so having somebody with that background to look at the business plan and how you can turn your passion into a growing business was so beneficial.”

She developed a roadmap for the business, undertook market research, a full product review and financial modelling for a commercial kelp farm. And she began applying for grants.

“We can’t really focus on marketing and developing new products until we have a more secure supply of kelp,” she explains. “So, we’ve put all our energy into this idea of farming,” says Jo Lane

Sea Health golden kelp granules. Photo: Catherine Norwood

Sea Health golden kelp granules. Photo: Catherine Norwood

Finding funding

Applying for grants has been time-consuming, but for a small business with big plans and limited resources, Jo has found it essential to secure funds needed for research and development.

Sea Health Products is technically a microbusiness and does not qualify for many grants because its turnover is too low, Jo explains. Most grants also require some level of co-contribution from the applicant, hence the loan the business has taken.

“But there are certainly grants out there,” she says. “I like to get in touch with the organisation giving out the grants to clarify whether my idea is suitable. In talking to them, you pick up certain language. It might be special keywords about employment opportunities or regional development, or whatever it is that the grant is hoping to achieve. You need to prove that you can achieve that so that your project fits the criteria.

“Grant writing can be a bit emotional if you apply for several and get rejected. And once you get the grant, you need to make sure that you have enough time to execute it and report on it as well.”

Jo’s tenacity has paid off. She has recently been successful with several grants.

These include €50,000 – about $80,000 – from the international Safe Seaweed Coalition to develop hatchery techniques for the development of a local seaweed industry. It was one of only 15 grants the coalition awarded worldwide in 2021.

The business also won a $10,000 prize from Investment NSW at the 2021 Innovation District Challenge, a university ‘pitchfest’ focused on industry collaborations. Jo has worked closely with the University of Technology Sydney as part of her kelp propagation research.

In February 2022, she successfully secured $115,000 in funding through the Australian Government’s Boosting Female Founders Initiative to help with the cost of the planning approvals process to establish kelp farms on her two marine leases.

Breeding progress

Jo has used knowledge gained from her Churchill Fellowship to develop growing techniques for golden kelp, with increasing success. Specifically, she has drawn lessons from the well-documented practices around sugar kelp (Saccharina latissima), one of the main kelps farmed in the Northern Hemisphere.

Back in Australia, as the COVID-19 pandemic raged in 2020, Jo and husband Warren Atkins focused on building a temperature-controlled breeding lab. This was based on facilities Jo had seen overseas and made use of Warren’s skills as a refrigeration and air-conditioning specialist – before he turned to full-time kelping with Jo.

“Previously, we’d been trying to propagate kelp in water that needed to be 15°C when the temperature outside was 38°C. When we began using refrigeration, that’s when we started to get success,” Jo says.

To adapt sugar kelp processes for golden kelp, they tweaked water temperature and the amount and timing of light and nutrients in the water to find the “sweet spot”.

“It has taken a lot of trial and error, but it’s paid off. We’ve had success in small batches, producing up to 20 metres of seeded twine. But we really need kilometres of this to set up a farm. Now it’s about replicating the experiments on a larger scale,” Jo says.

As well as their own lab at Tilba Tilba, they have been working with the Sydney Institute of Marine Science (SIMS), where they have access to autoclave equipment to help reduce contamination of kelp cultures. In March 2022 they put their first kelp plants on lines into the water on the SIMS marine research lease at Chowder Bay in Sydney Harbour, marking a significant milestone for the business.

They are also collaborating with a Tasmanian scientist who has experience with kelp propagation to develop the reliable, repeatable processes needed to scale up for farming.

“We can also potentially help with seaweed restoration projects, and we’re excited about that,” Jo adds. “We’ve noticed a decline in golden kelp along the south coast of NSW. There are probably several reasons – changes in water temperature, an increase in sea urchins feeding on the kelp and a decline in the population of urchin predators such as rock lobsters.”

Like many other seaweeds, golden kelp releases millions of spores because the chance of spores meeting and being fertilised in the ocean is very small. In a laboratory, the chances of fertilisation are much higher. A single drop of water underneath the microscope can contain hundreds of plants, which Jo suggests could be used for farming or to replant wild stands of kelp if needed.

Environmental planning and impacts

As the breeding advances, Jo is also embarking on the planning approvals process for the two marine leases she successfully tendered for in December 2021. One is at Pambula, the other at Bermagui.

These are among the first marine leases awarded under the 2018 NSW Marine Waters Sustainable Aquaculture Strategy, which opens new marine areas to aquaculture.

The strategy streamlines approvals through the NSW Department of Planning and Environment. Previously, any marine-based project required separate approval from up to 11 different government agencies.

Jo is somewhat daunted by the process ahead, which includes scoping documents and a full environmental impact statement. “Our seaweed farms have the same status as a ‘significant development’ or ‘major project’,” she says. “It’s on par with the Barangaroo waterfront precinct in Sydney, a new water treatment plant or an airport. But, hopefully, it will be straightforward.

"We're putting an anchor and some chains in the water and the plants are a native species. This is a proven technique that works overseas. We are just copying a successful model.”

Collaboration and community

Collaboration and community consultation will be essential to the planning process and to Jo’s long-term plans for the business. After developing the techniques to provide seeded kelp for her own farms, her vision is to become a hatchery hub, supplying others who want to farm kelp.

This concept is influenced by the industry-led GreenWave regenerative ocean farming program Jo saw in the US. GreenWave provides training and support to help new seaweed farms get started and creates a network of small businesses that are contributing products and positive environmental outcomes to their regional economies.

She sees a structure similar to that of the oyster industry in Australia, with central hubs and hatcheries supporting families who run their own farms. But she is concerned about the potential for “big players, with big money” to jump into seaweed farming and change the landscape.

Collaboration is key to her vision for new sustainable enterprises and a sustainable industry. “Kelp is such a positive resource, with so many benefits”.

“Growing kelp can reduce ocean acidification, provide habitat for fish and other marine species, and draw down some carbon dioxide.

“Once you harvest it, there are so many things you can do with it. You can use it for food, fertiliser or cosmetics extracts; you can put it into building materials, furniture, bioplastics and, potentially, biofuels.”

Scientists working on these diverse products include those involved in Australia’s Marine Bioproducts Cooperative Research Centre (MBCRC), which was announced in June 2021. Sea Health Products is an official partner in the MBCRC and its ‘sustainable biomass’ research stream. It will also research processing technologies and product development for seaweeds and other marine organisms.

[ Read more Cooperative research to kickstart marine bioindustries ]

“To make all those clever things, we’re going to need a really big supply of Australian kelp, and that’s what I am interested in – creating a sustainable biomass so we can supply it to other people to do these things.

“I certainly see what I’m doing as part of a bigger industry, and it has to be, in order to have the impact we need to address the environmental and climate issues we’re facing right now,” says Jo.

This is an edited version of an article originally commissioned by AusIndustry and has been reproduced here with permission.

Produced in Shorthand by Fiona James for Coretext.

View other Shorthand stories by Coretext here.