Master

the art of filleting

A new online guide provides the techniques and species knowledge to help recreational fishers (and others) produce restaurant-quality fillets from their catch in no time

A plate stacked with deboned full-flesh fillets ready for the pan or grill is the goal of many fishers. And to help upskill the nation’s recreational fishers, two enterprising Western Australians, Konway Challis and his brother-in-law Rick Knight, have created an extensive online library of filleting tutorials.

The pair has created Fillet Fish Australia to show people how to fillet Australian species quickly and efficiently and with minimal or no waste.

Challis and Knight both grew up in professional fishing families and have worked extensively as professional filleters for WA seafood processors. Challis is still involved in the seafood industry, running his own seafood business, and Knight is now a software developer.

Their video tutorials are free to view and range from beginner to advanced techniques and styles. The pair say their objective is to make filleting an enjoyable, more productive finale to a day’s fishing. They want to improve people’s understanding of how to do it well, and the importance of ‘recovery rates’.

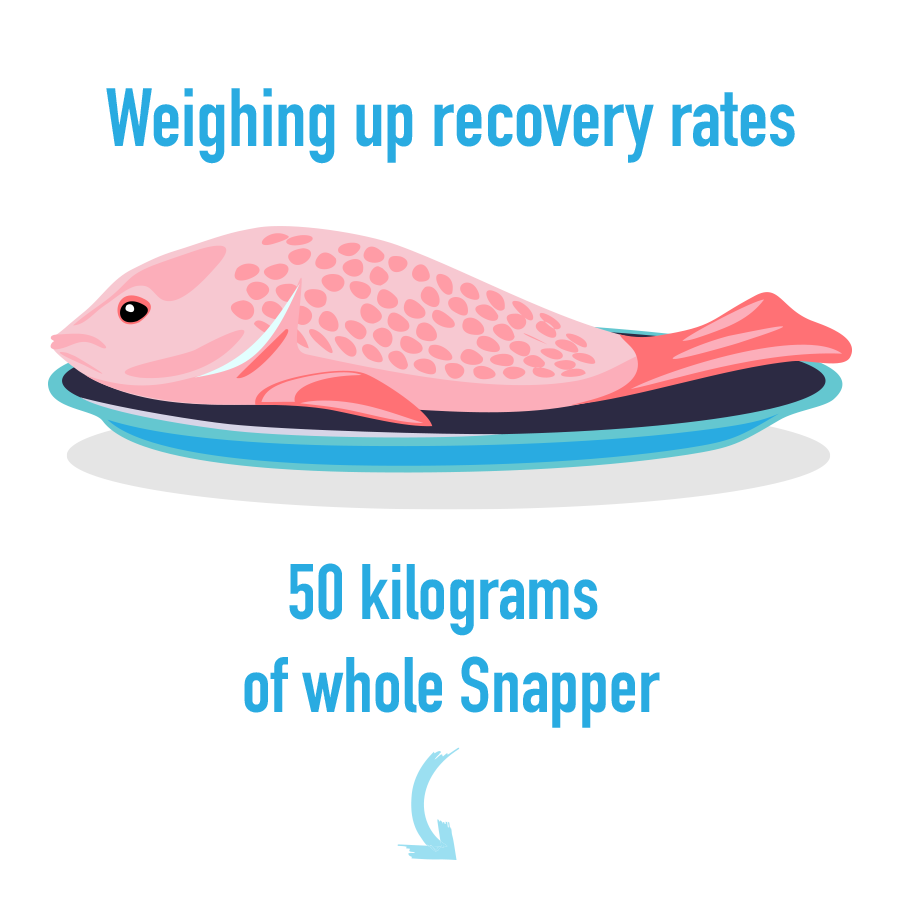

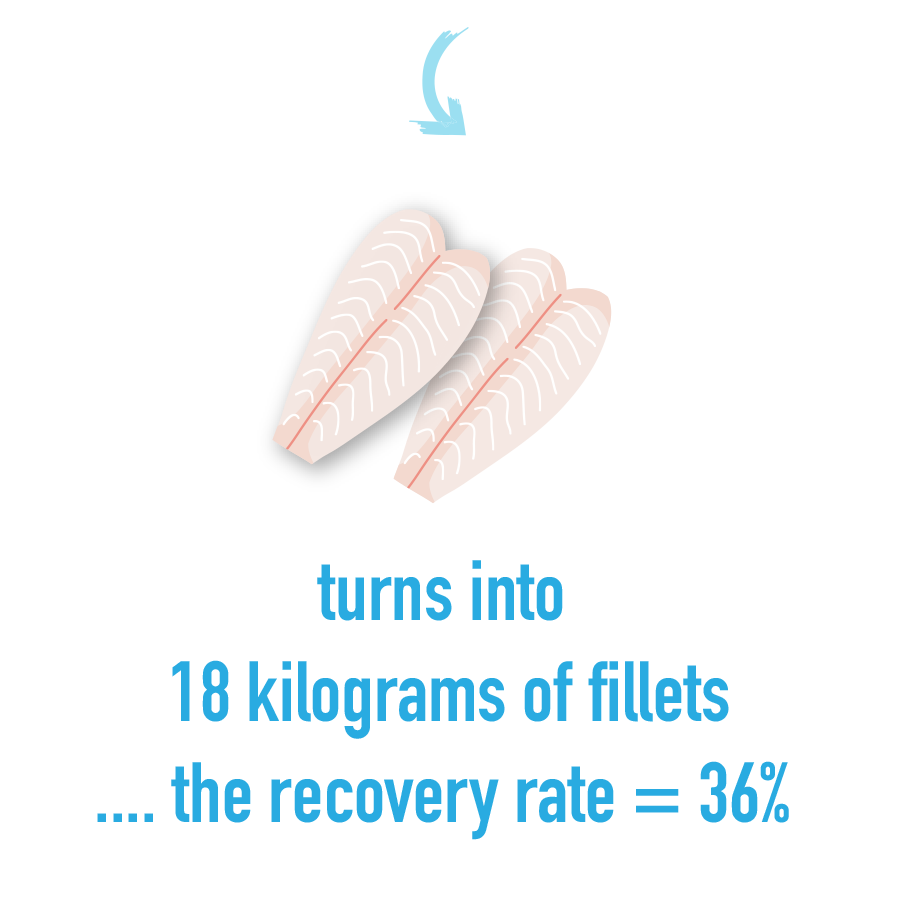

Weighing up recovery rates

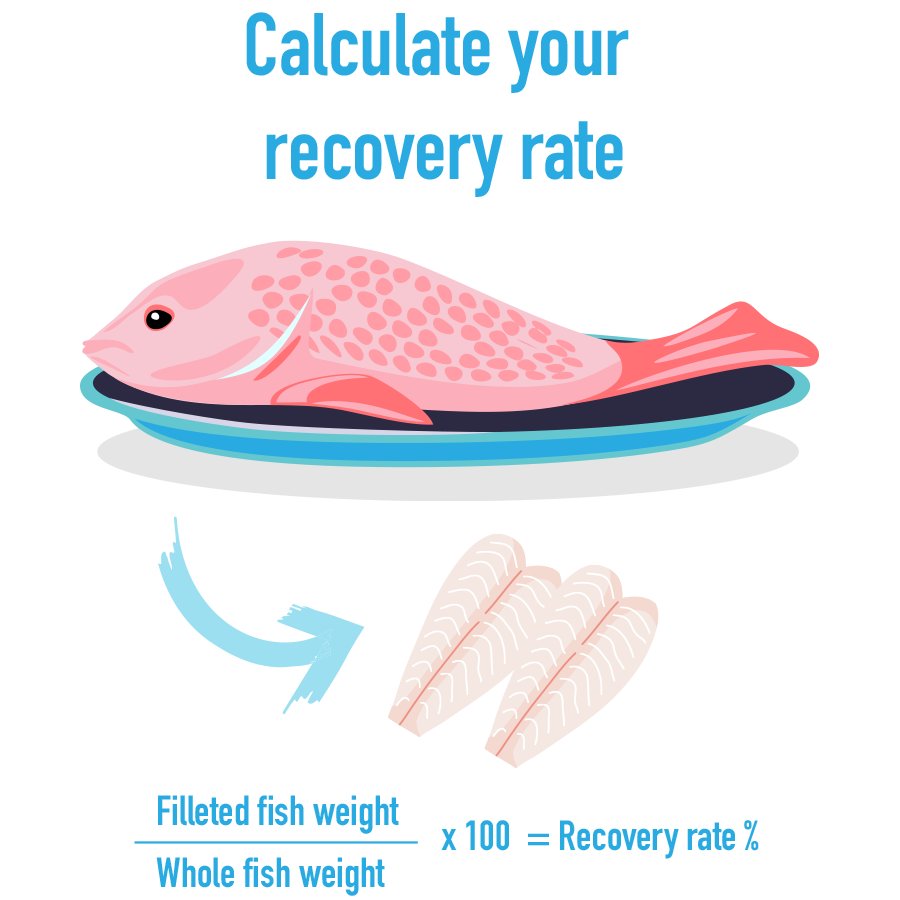

Recovery rate refers to the weight of fillets as a percentage of the weight of the original whole fish.

For example, their website explains that if you were to fillet 50 kilograms of whole Snapper you would end up with 18 kilograms of fillets; the recovery rate is 36 per cent. The formula is ‘weight out’ (after processing) divided by ‘weight in’ (before processing), multiplied by 100; for example, 18/50 × 100 = 36 per cent. For professional fishers and processors, even a two per cent difference in the recovery rate per fish can be the difference between a marginal or profitable business.

The Fillet Fish Australia website features a chart listing the optimum recovery rates for different species and a calculator for estimating how many servings a whole fish of a particular species and size should produce, if filleted properly.

Challis and Knight say the key factors affecting recovery rates are:

- the condition of the seafood;

- the sharpness of the knife; and

- the skill of the filleter.

Maximise value

Challis is keen to point out that recovery rates are not the full picture; the rest of the fish still has use and value.

“While Aussies tend to prefer fillets, a lot of cultures cook the whole fish, especially if it is baked. The wings are good to barbecue, and the heads and frame can be boiled to make fish stock, fed to pets or used as bait to catch other seafood such as crabs.”

Challis says he sells the pieces he removes in filleting to a restaurant supplier for use in Asian cooking.

In addition to the filleting videos, the Fillet Fish Australia website has short articles covering knives, safety, optional styles and techniques for people’s different needs and preferences. It discusses the advantages of catching, or buying, whole fish and filleting them yourself – especially if you can make use of the rest of the fish – as well as how to pack and store fillets.

The filleting styles covered by the tutorials are widely used in the seafood industry as they are suited to a range of species, have good recovery rates and are safe for the user.

Sharing skills

For Challis, the website has been a labour of love born from his observations of poor and wasteful filleting practices and the wide skills gap between the average fisher and professionals in the seafood processing sector, which he sees as unnecessary.

“I’d look in boat ramp bins at the end of a day and see so many usable pieces of fish and think what a shame that people have spent all that money on boats and gear, learning knots and other boating skills, but not learnt how to properly treat their catch.”

This sparked the idea for Challis and Knight.

“We could both see the need and were thinking about a website for quite a while before finally doing something,” says Challis.

He explains how they were initially put off by the seemingly large number of online filleting videos. “But they were mostly amateurs who didn’t really know what they were doing; just videoing what they do and sometimes passing on bad techniques.

Filleting a Banded Wobbegong.

Filleting a Banded Wobbegong.

Konway Challis filleting an Atlantic Salmon; first fillet being removed and placed on the filleting bench.

Konway Challis filleting an Atlantic Salmon; first fillet being removed and placed on the filleting bench.

A Red Emperor being filleted – about to cut over the raised section of the spine, following the frame of the fish closely with the knife.

The first fillet is about to be removed by running the knife along the ribcage and then cutting out at the belly. This is an over-the-rib technique.

Pin boning an Atlantic Salmon. Industrial tweezers are used to remove all the individual bones that run approximately halfway down the fillet.

Dry-filleted Atlantic Salmon portions, ready to eat.

“So, a few years ago, after seeing what was out there and realising something better was needed, especially for local species, we bought

a good quality video camera and teamed up … I did the filleting and Rick did the videoing and website development.”

Local content

“So far we’ve made 103 videos, concentrating on WA species, but the website analytics show that our audience is worldwide,” says Challis. “We cover filleting, skinning and pin boning, and all the skills you need to produce completely boneless fillets.”

In the videos, he discusses the importance of knowing a species’ bone structure, and the appropriate techniques and specificity of knife cuts for that species.

“Because we cover all of the most popular West Australian and Australian species, you can watch a video for the actual fish you have caught.”

The value of the Fillet Fish Australia tutorials is becoming increasingly recognised by bodies such as Recfishwest. It comes at a time when reducing food waste has become a global concern and a key component of making food industries more sustainable.

Recreational fishing is one of the great Australian outdoor activities – estimated to be worth $2.56 billion to the economy – but the value of the actual seafood caught could be increased considerably if more amateur anglers take the challenge to improve their filleting skills.

Produced by Coretext

This story was first published in the Fisheries Research and Development Corporation's Fish Magazine Vol29 Issue 4 (December 2021).