Restoring seagrass meadows

Beach lovers, ocean enthusiasts and recreational fishers around the country are joining forces with marine researchers to restore Australia’s vital seagrass meadows.

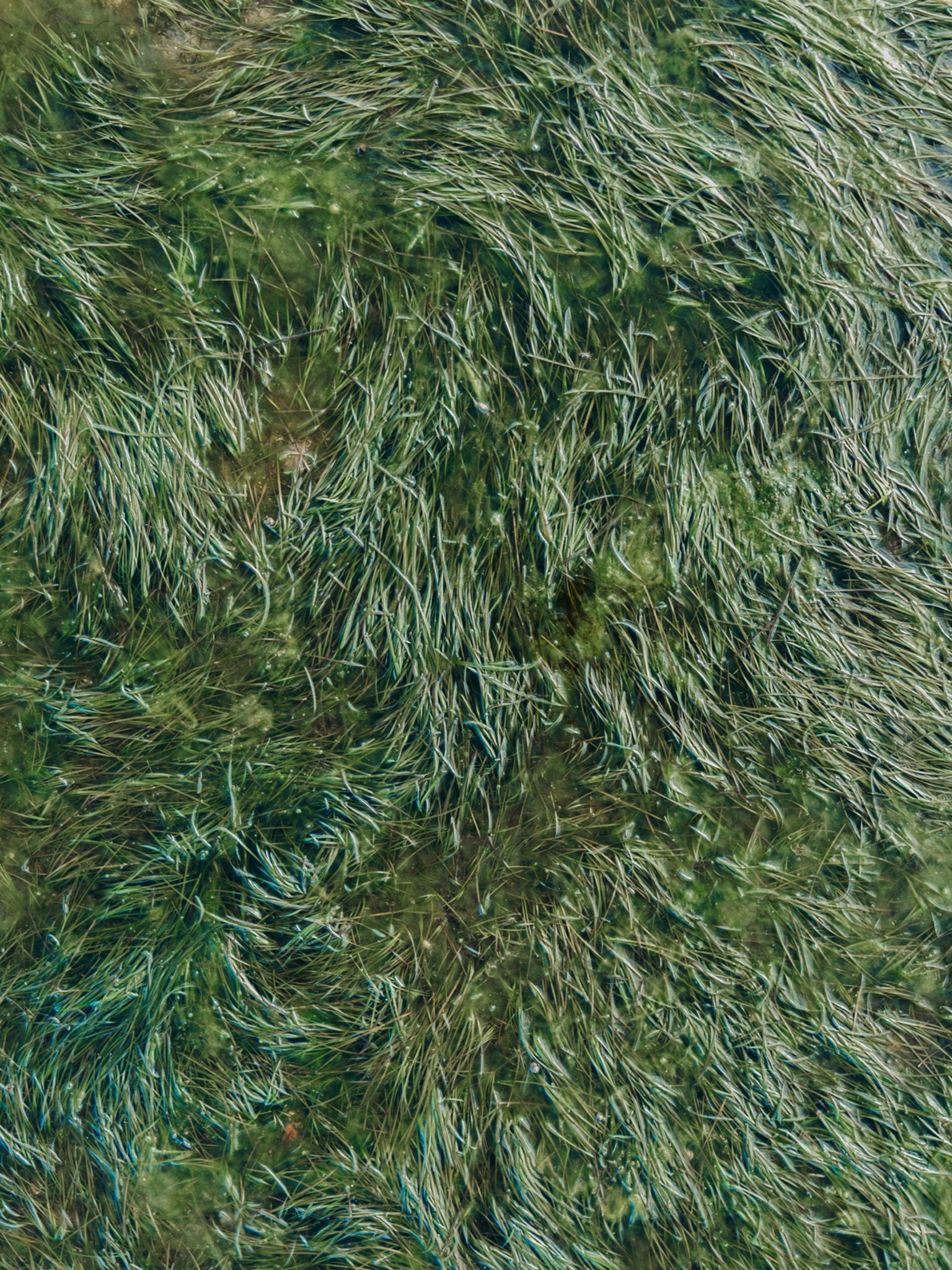

Coastal seagrass meadows are among the most productive ecosystems on earth, providing food, shelter and breeding grounds for hundreds of marine species, including important commercial and recreational fish and crustaceans.

Seagrasses improve water quality by trapping sediment and recycling nutrients. They protect shorelines from erosion, and store carbon up to four times faster than forests on land.

Australia has lost about 30 per cent of its seagrass meadows – and up to 85 per cent in some places – representing hundreds of thousands of hectares of critical natural habitat and carbon sinks.

Seagrass research for restoration is a relatively new field of study, but is quickly expanding with a growing number of restoration initiatives underway. Local projects are bringing together thousands of people in communities around Australia to protect and restore seagrass meadows.

Why have seagrasses declined?

Seagrasses are most commonly found in estuaries and bays where there is relative protection from strong tides. This also makes them susceptible to the impacts of urbanisation and polluted runoff that contaminates inshore waters and makes it harder for them to get the light they need to grow. Sediment in the runoff can also smother plants.

Boating activities contribute further, with boat propellers and mooring chains regularly causing damage. Disease affects some seagrass beds, and there is a growing impact from extreme weather events both at sea and on land. Flooding, in particular, brings high sediment loads and large freshwater flushes into estuaries and embayments, which can kill seagrasses.

Seeds for Snapper program volunteers and OzFish Unlimited staff sort the fruit of Posidonia australis seagrass, which will release seeds that are used to help restore local seagrass meadows. Photo: OzFish

Seeds for Snapper program volunteers and OzFish Unlimited staff sort the fruit of Posidonia australis seagrass, which will release seeds that are used to help restore local seagrass meadows. Photo: OzFish

A diver collects Posidonia fruit from a meadow in deep water. Photo OzFish

A diver collects Posidonia fruit from a meadow in deep water. Photo OzFish

Seagrass species

Australia is home to more than 30 species of seagrass – more than half of the 70 or so species known globally. However, there are two key species that are the focus of long-term research and restoration underway:

• Posidonia australis, also known as ribbonweed or fireball weed

This is a slow-growing subtidal seagrass endemic to Australia. Its leaves are the widest of all Australian seagrasses. It makes extensive underwater meadows at depths of one to 15 metres and is found along the southern Australian coastline from Wallis Lake in New South Wales to Shark Bay in Western Australia.

• Zostera muelleri, also called eelgrass, garweed and dwarf grass-wrack

This is a fast-growing intertidal species found along the east coast, from northern Queensland, south to Tasmania and west to South Australia It is also found in New Zealand, Papua New Guinea, and areas of the eastern Indian Ocean and the southwest and western central Pacific Ocean. It has long, strap-like leaves and prefers protected mud or sand flats.

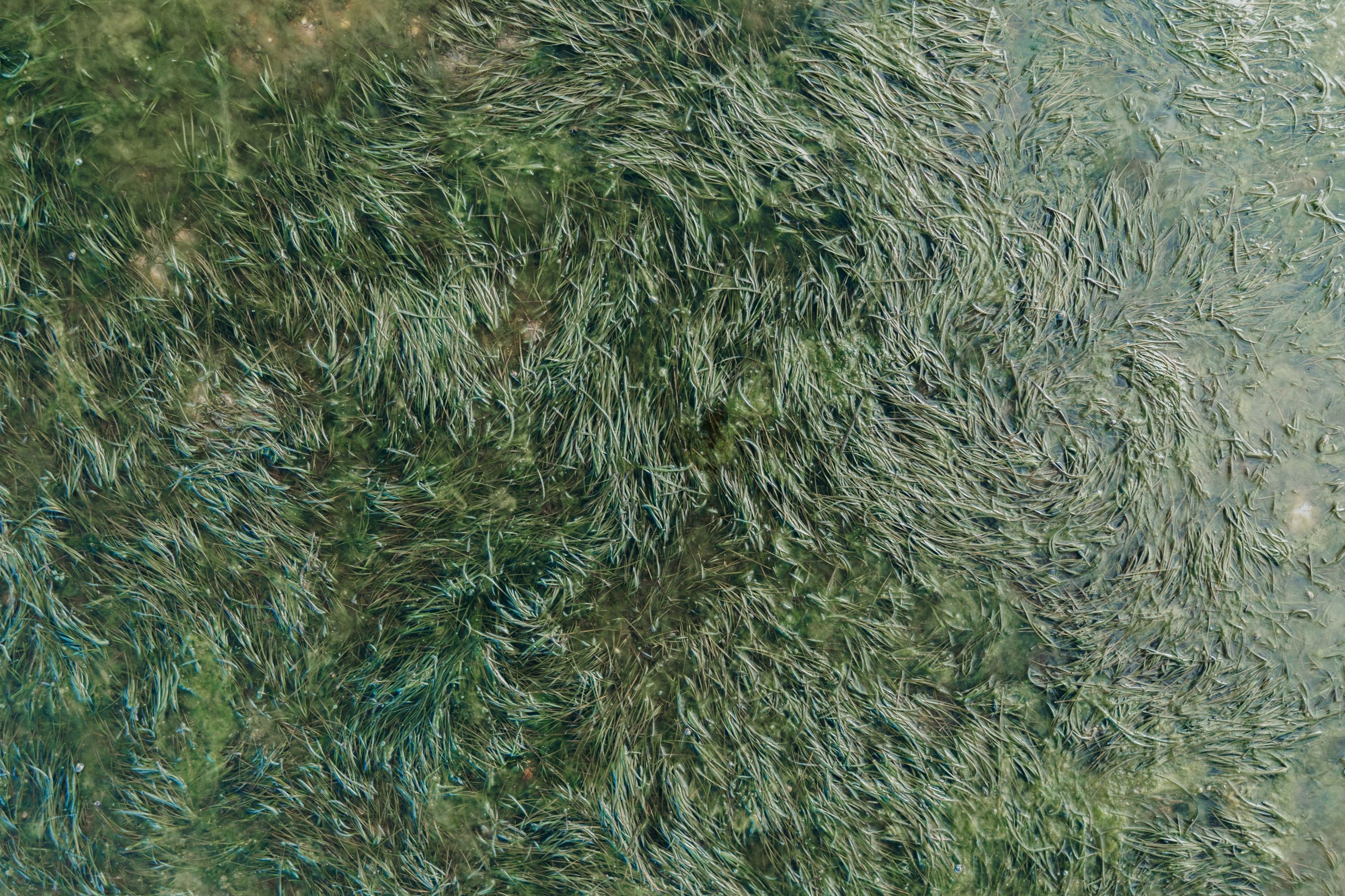

Posidonia australis. Photo: OzFish

Posidonia australis. Photo: OzFish

Zostera muelleri. Photo: OzFish

Zostera muelleri. Photo: OzFish

Emerging research

Recreational fishers have been quick to support seagrass initiatives, given the link between habitat and popular fish species. The recreational fishing conservation charity OzFish Unlimited is leading restoration efforts in several states and encourages its members to help with initiatives being led by the community.

After a flurry of research in the 1980s and 1990s investigating the role of seagrasses in ecosystems, research in active restoration techniques is a relatively new area of study.

Cassie Price is Director of Habitat Programs for OzFish and says the science of seagrass restoration is still evolving.

“Even just five or six years ago, few environmental scientists thought it was possible to restore seagrass at the scale needed to re-establish functioning seagrass meadows.

“But now we’re identifying sites all around the country where we think that is possible,” says Cassie.

“With seagrass and restoration, the process is often different even when it’s the same species, it often acts very differently in different locations. So, you’re often working on a case-by-case basis for the best methods to use at each site.”

Nothing makes this clearer than Posidonia australis, the species that is the focus of the OzFish flagship seagrass program.

In the south-east of Western Australia and in South Australia, Posidonia produces large quantities of fruit and seeds, which can be used to direct seed restoration sites.

But in other parts of the country, the same species rarely flowers and relies instead on rhizomes to reproduce, which makes restoration far more difficult.

Seeds for Snapper

Seeds for Snapper builds on research from the University of Western Australia (UWA), which is an ongoing partner in the program, along with OzFish, corporate retailer BCF, Western Australia’s peak recreational fishing body RecfishWest and other community supporters.

The program launched in 2018 at Cockburn Sound near Fremantle, where more than 80 per cent of seagrass meadows have disappeared, and where Snapper, a favourite with rec fishers, were also in decline.

Each year from late November to early January, when Posidonia produces fruit, volunteers gather to collect them from beaches and from fruiting plants in deeper water. The fruit are kept in large tanks which allow them to ripen before the seeds are dispersed into selected restoration sites.

In six years, the program has collected 5 million fruit from Posidonia plants, and dispersed 1.7 million seeds into Cockburn Sound, scaling up the original UWA trial site from 100 square metres to several hectares.

In 2020, OzFish expanded Seeds for Snapper to South Australia, with a program in Adelaide’s Gulf St Vincent, and another within the Fleurieu Peninsula in 2022. The selected seagrass sites in South Australia are open to the ocean and seeds are handsewn into sand-filled hessian bags to help anchor them in place on the sea floor against strong tides.

Community participation

Cassie highlights the importance of community volunteers, from the boaters, fishers and divers to beach walkers and the many local businesses who support OzFish programs, in addition to the major sponsors and partners.

“It’s the hundreds of volunteers that make these projects work. Restoration is very labour-intensive, and it’s challenging to get funding to do things at the scale we’d like to,” she says.

With its focus on recreational fishers, Seeds for Snapper has provided a valuable opportunity to expand fishers’ perspectives, linking habitat to an iconic species that has struggled in numbers over recent years.

“Juvenile snapper rely on those seagrass beds in various places to kick-start their life cycle. This project has really helped recreational fishers to understand the value of seagrass habitat and the role in the lifecycle for fish, even if it’s not where they would catch their fish.”

Seagrass meadows are an important nursery ground for many popular fish species. Photo: OzFish

Seagrass meadows are an important nursery ground for many popular fish species. Photo: OzFish

Each year volunteers gather to collect Posidonia fruit for the Seeds for Snapper project in Western Australia. Photo: OzFish

Each year volunteers gather to collect Posidonia fruit for the Seeds for Snapper project in Western Australia. Photo: OzFish

Researchers continue to assess different establishment techniques for the restoration of seagrasses. Photo: OzFish

Researchers continue to assess different establishment techniques for the restoration of seagrasses. Photo: OzFish

Posidonia in New South Wales

New South Wales has also suffered from an extensive decline in its seagrass meadows. Professor Adriana Vergés from the University of NSW (UNSW) says about half of the state’s Posidonia meadows have been lost.

The decline is so severe in several estuaries around Sydney that the species is listed as endangered ecological communities under both state and federal legislation.

Endangered seagrass ecological communities in NSW. Source: Operation Posidonia

Endangered seagrass ecological communities in NSW. Source: Operation Posidonia

In New South Wales, Posidonia rarely flowers or fruits, leaving restoration efforts to focus on transplanting seagrass fragments that have viable roots or rhizomes attached.

Further complicating this work is that many of the factors that have caused the decline – chiefly coastal development and boating activities – continue to occur.

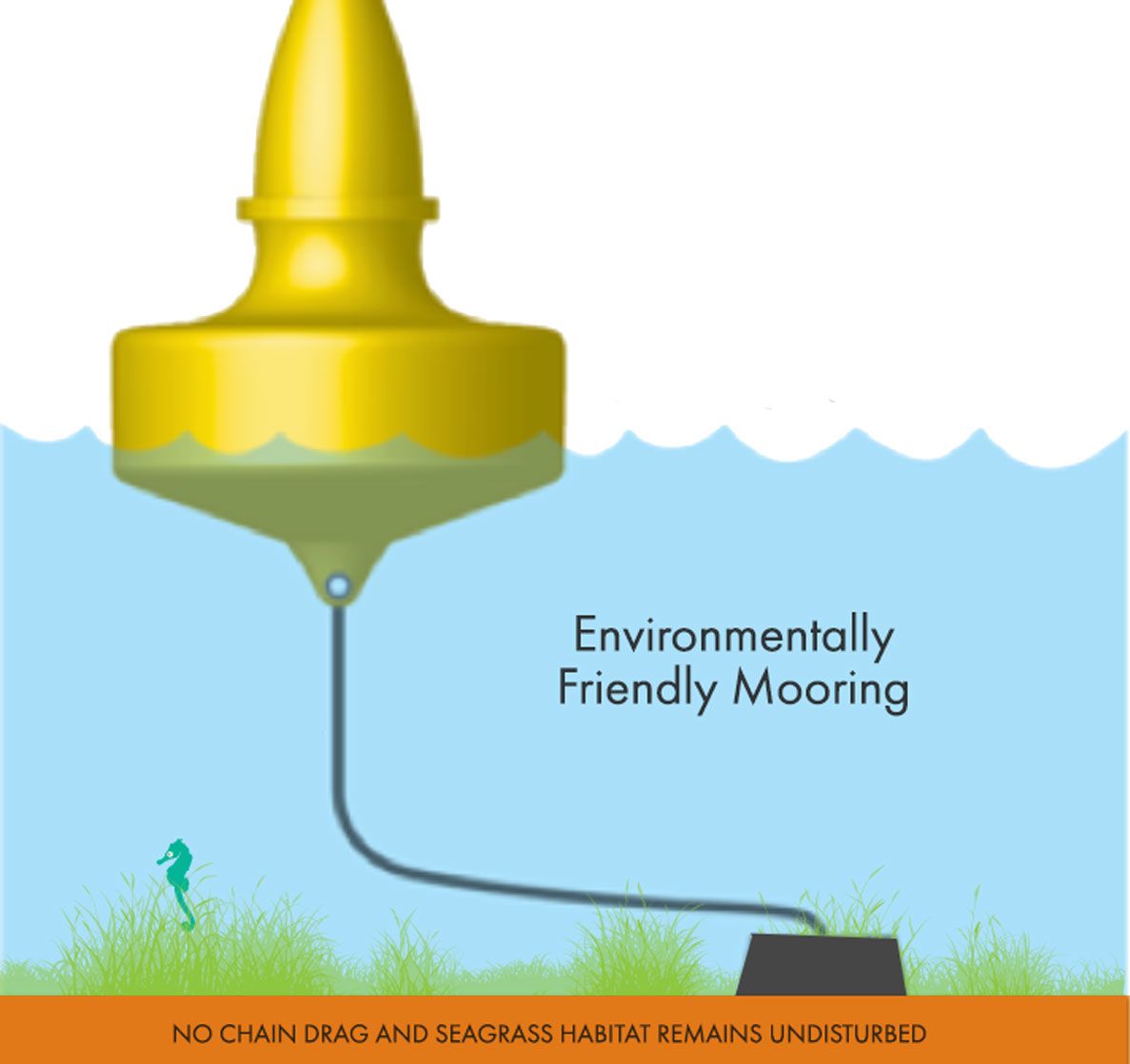

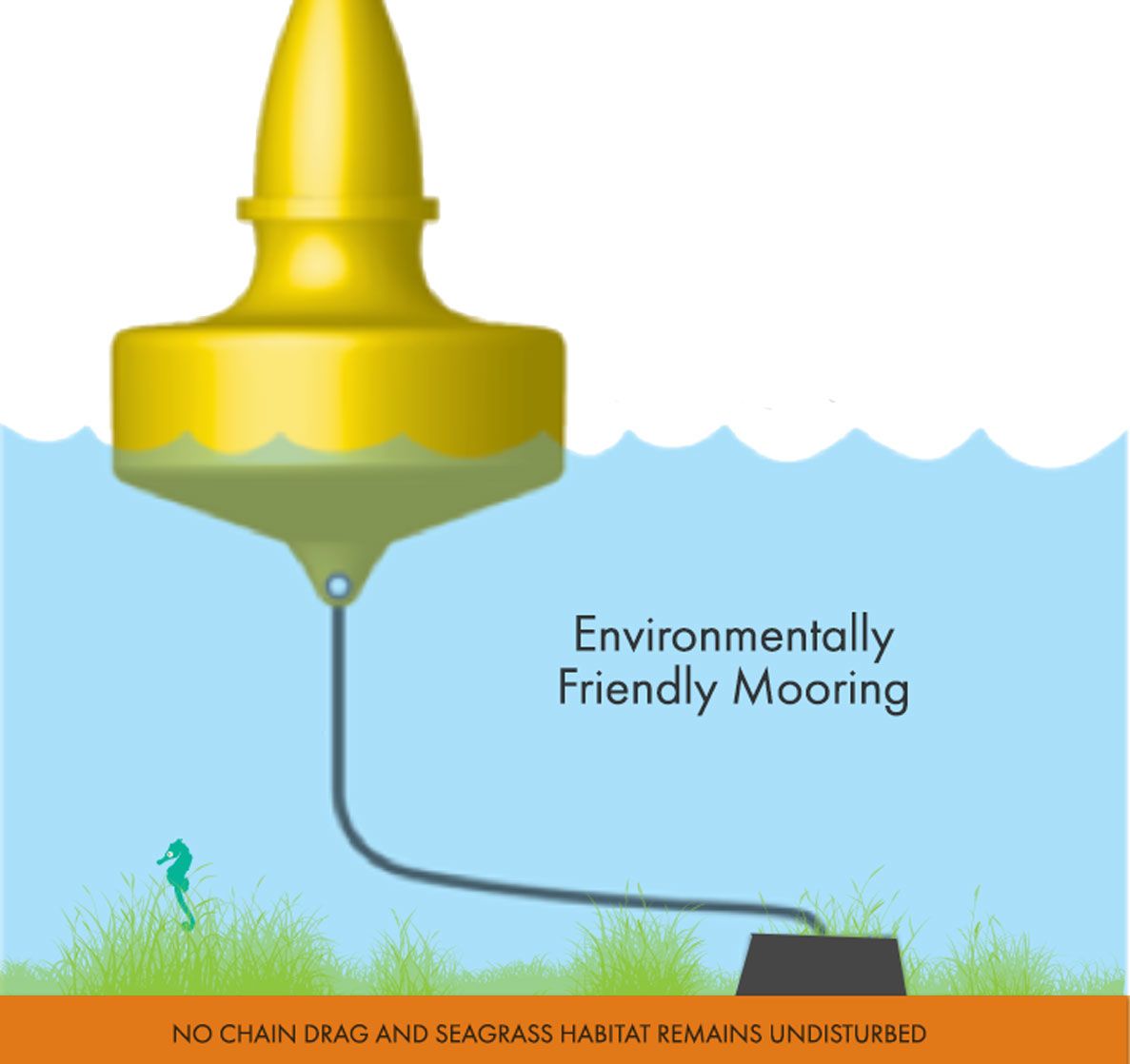

For example, heavy chains commonly used on swing moorings for boats repeatedly slice through the seagrass beneath them, leaving scars on the seabed that expand as the moorings – and chains – move with the currents and tides.

“So we’ve been collaborating with the NSW Department of Primary Industries to trial environmentally friendly moorings that use a synthetic, neutrally buoyant rope rather than chains, in conjunction with seagrass restoration,” says Adriana.

Gathering seagrass fragments

Adriana’s team began their first restoration trial at Port Stephens from 2018 to 2020, also engaging with community members who helped to collect about 2000 storm-cast seagrass fragments from beaches. Divers from UNSW then replanted viable fragments into the ocean floor where seagrass had become sparse.

“We showed that the plant fragments can survive. After nine months we started to see good growth and 70 per cent survival after one year,” says Professor Vergés. “This gave us a proof of concept that this approach could work.”

Her team applied this technique to another site, at Lake Macquarie, although the project wasn’t successful there. She attributes this to sediment and water turbidity caused by boat wash, and significant areas of mooring scars in the seagrass beds.

“But we’re not giving up. We’re planning some experiments this year to understand those processes better so that we can develop solutions,” she adds.

The successful restoration plots at Port Stephens also suffered a setback after flooding in July 2022. The freshwater flushes and sediment in floodwaters damaged both natural and restored meadows equally, with about a third of meadows there lost.

Restoring Sydney Harbour

In the coming year a major funding initiative will see new Posidonia sites established as part of Sydney Harbour’s three-year Project Restore, which is the largest harbour restoration initiative in the world.

The $4.5 million Project Restore is part of the $6.6 million Seabirds to Seascapes initiative, funded by the NSW Environmental Trust.

Along with Posidonia, Project Restore will also focus on endangered populations of White’s Seahorse, Little Penguins, Green Turtles, pipefish and seadragons – all of which rely on Posidonia for habitat.

“One issue that we have in Sydney Harbour is that there’s so little Posidonia left that we have to bring it in from nearby estuaries, from Pittwater and from Port Hacking,” says Adriana.

“We’re now at the early stages of engaging with communities in those two estuaries so that we can start collections. We’ll be doing essentially the same thing that we did in Port Stephens. We’ll have collection stations, and we will involve local community groups, individuals and schools in the collection of the seagrass fragments for planting by divers in Sydney Harbour.”

Mooring scars in Posidonia meadows in Lake Macquarie. Photo: Tim Glasby

Mooring scars in Posidonia meadows in Lake Macquarie. Photo: Tim Glasby

Traditional swing mooring. Source: Operation Posidonia

Traditional swing mooring. Source: Operation Posidonia

Zostera in Victoria

In Victoria, the restoration research has focused on Zostera muelleri. Researchers from Deakin University, in partnership with Melbourne Water, have spent the past six years developing restoration techniques for the species in Western Port Bay, where up to 70 per cent of meadows were lost over 40 years ago.

Deakin’s Dr Craig Sherman says the university’s earlier research to evaluate seagrasses in Port Philip Bay showed that meadows there were generally healthy. But that wasn’t the case in Western Port Bay.

Based on historical images and extensive mapping, it appears the Western Port’s seagrass ecosystems reached a tipping point in the 1980s, after decades of cumulative stresses, including increased sediment loads as a result of agricultural expansion and urban development.

As the waterway manager for Western Port’s catchment, Melbourne Water has been a key partner in the seagrass research. Sediment loads into Western Port Bay have been significantly reduced in recent decades, and some seagrass meadows have started to recover naturally with improved water quality.

But other areas haven’t recovered at all. Deakin and Melbourne Water researchers have been evaluating the potential of plant fragments and seeds collected from local meadows for use in assisted restoration. Craig says they’re leaning towards regeneration from seeds, either directly into the field or following nursery propagation of seedlings, which will allow for larger-scale restoration.

Trials have included a series of seed treatments to identify what triggers the germination. As a result they can now reliably germinate 60 per cent of seeds, and up to 80 per cent in some cases. The resulting seedlings are then raised at the Advanced College Nursery on the Mornington Peninsula before planting out into trial sites.

Scaling up efforts

“In addition to planting out seedlings, we’re trialling all kinds of experimental approaches, always keeping in mind what might be scalable,” Craig adds.

“Zostera likes to have sediment around it to germinate; it won’t grow from seed sitting on the surface. So we’re looking at a Dutch technique that puts a mixture of sediment and seed into a caulking gun. The mixture is then squeezed directly into the floor of the bay, and you can cover a lot of ground quickly.

“Researchers at Central Queensland University have also been using what are basically mudballs, which can be dropped into the water. Although they are working with a different Zostera subspecies, we’re testing whether this will work for us.”

Western Port has two productive donor sites that provide seed from healthy seagrass meadows, and there are five experimental locations in degraded meadows that are the focus of restoration efforts. In the coming year, Deakin and Melbourne Water plan to scale up from restoration experiments on plots a few metres square to sites that are hundreds of metres square.

Craig’s long-term vision for restoration includes new business opportunities for nurseries to grow seedlings for replanting or commercial production of other seeding products, such as mudballs, to simplify restoration processes. Eventually, he hopes there will be job opportunities for ongoing restoration work, just as there are for land-based revegetation.

He sees more appetite at both the federal and the state government levels for preserving marine habitats that are tightly linked to fish habitats, providing a powerful driver and value for the community.

“There’s also a growing realisation of the wider values of seagrass habitats, such as carbon sequestration, and that if they're feasible to restore we need to be doing that.”

Craig Sherman at Deakin University’s Queenscliff research centre where Zostera seed is being separated from the other plant matter. Photo: Catherine Norwood

Craig Sherman at Deakin University’s Queenscliff research centre where Zostera seed is being separated from the other plant matter. Photo: Catherine Norwood

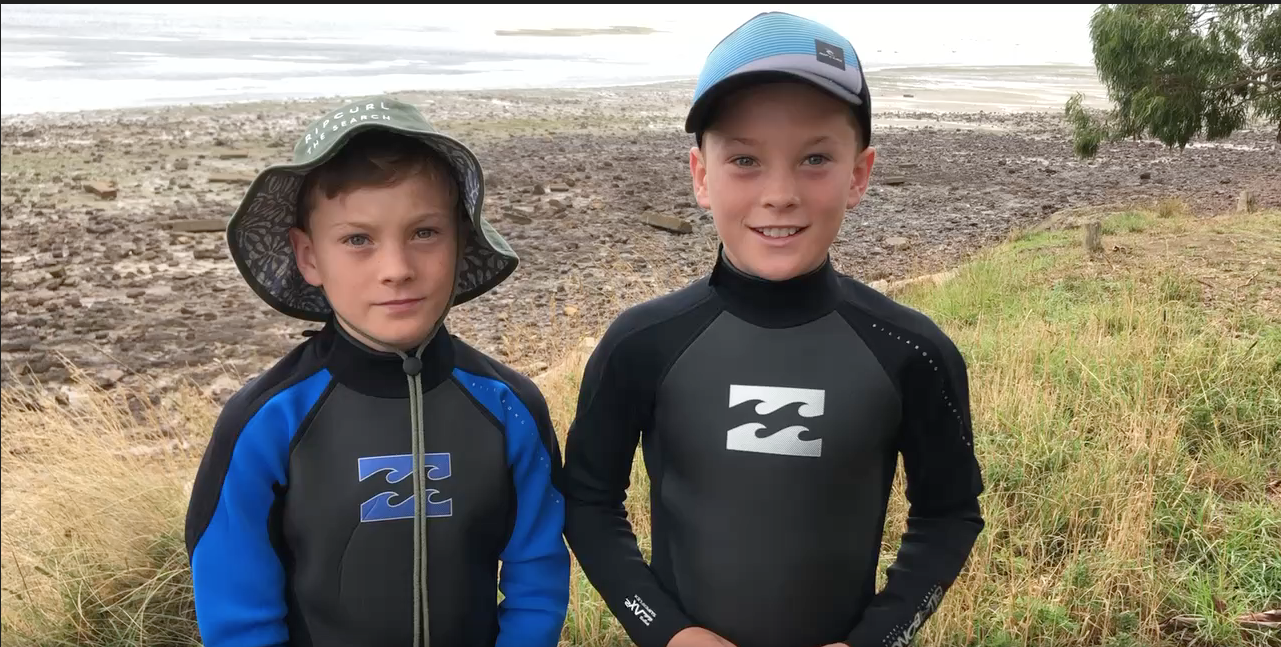

Deakin University researchers and volunteers collect Zostera seeds in Western Port Bay. Photo: Catherine Norwood

Deakin University researchers and volunteers collect Zostera seeds in Western Port Bay. Photo: Catherine Norwood

Visual Story: Catherine Norwood, Fiona James at Coretext